More than 250 libraries from across the state of Pennsylvania--both urban and rural--responded to our survey.

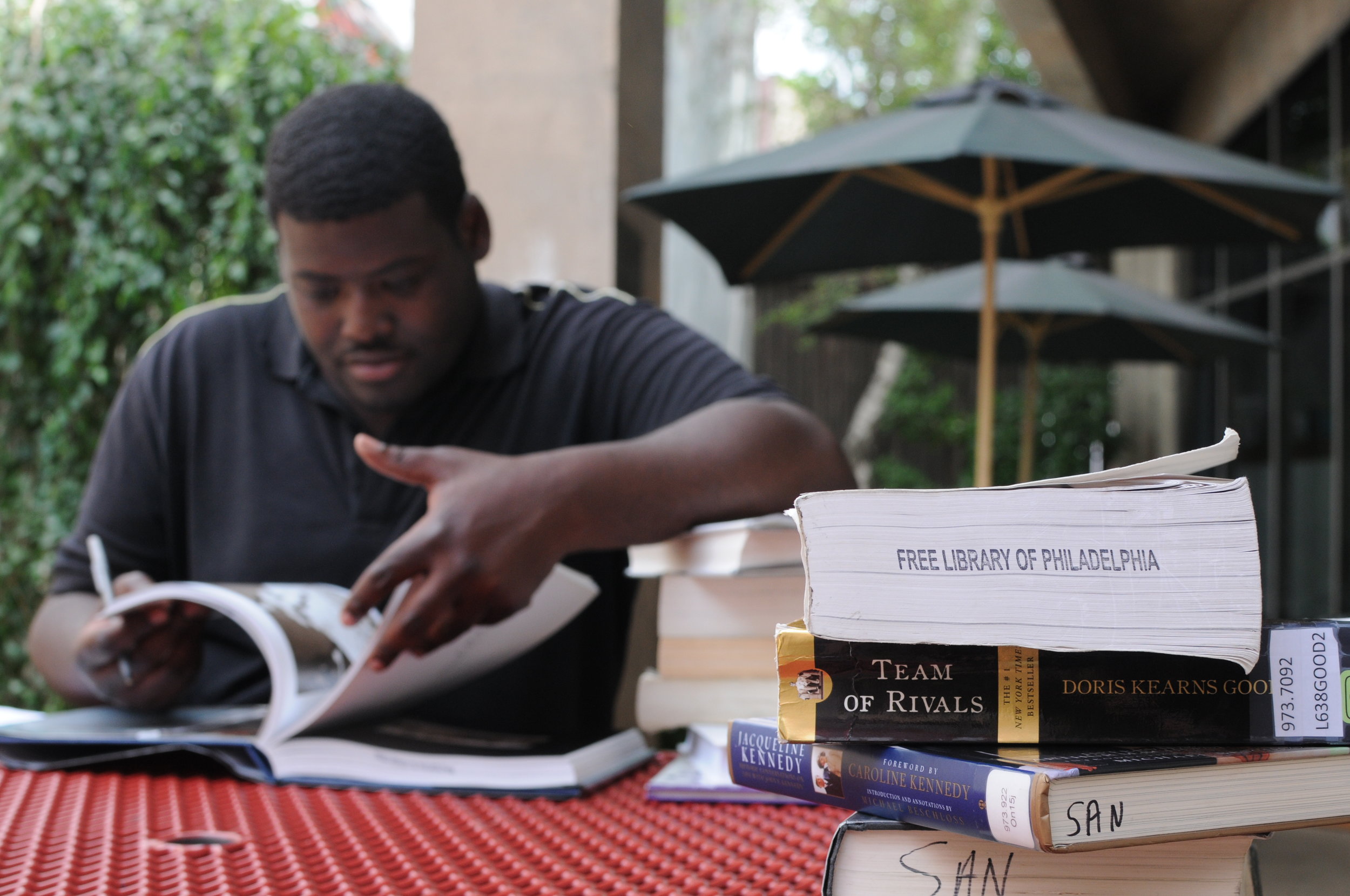

In our work with the Free Library of Philadelphia, we have learned that library staff are highly attuned to the needs of their communities. By responding to queries throughout the day, librarians learn about patrons’ concerns, hopes, needs, and priorities. Library staff also become vital community sentinels--people who can “take the temperature” of a neighborhood in order to report on current community health concerns.

Building on our Philadelphia research, we capitalized on librarians’ roles as community sentinels by conducting a web-based survey of all public library directors in the state of Pennsylvania. We aimed to understand how community health concerns varied between urban and rural areas across the state. We learned that library staff actively address the social determinants of health, whether they operate in remote rural areas or densely populated urban centers.

The full results of this survey were released today in the CDC’s online journal, Preventing Chronic Disease. The survey further explores the daily work practice of public library staff, with a focus on the social determinants of health. We received more than 250 responses from libraries across Pennsylvania. Mirroring what we have seen in Philadelphia, respondents from both urban and rural libraries indicated that they frequently interact with library patrons about their health and social needs - including help with employment, enrolling in social welfare benefits, and finding food - but that they feel underprepared by their professional training to address many of their patrons’ needs.

Very importantly, we learned that 12% of Pennsylvania’s public libraries had experienced opioid overdoses in the past year. This finding is important in two ways. First, it shows that libraries are deeply affected by the opioid crisis and need resources and training to manage this public health emergency. Second, this finding offers “proof of concept” of the idea of library staff as community sentinels. Through this survey, and with the help of library staff, we identified clear insight into a public health issue that calls for rapid response.

The results of this study inspired our team’s current work, in partnership with the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, on overdose awareness and reversal trainings at the Free Library of Philadelphia. We also trained about 75 librarians who attended the Public Library Association annual meeting, held in Philadelphia in March 2018. Lastly, we are preparing to roll out a national version of the survey, which will include a deeper dive into the impact on public libraries of the opioid epidemic and immigration issues. Stay tuned!

This survey was conducted with support from the CEAR Core of the UPenn CTSA. You can read the full text of the study here and listen to the CDC audio podcast of an interview about the study with Dr. Eliza Whiteman here.

Post by Eliza Whiteman